Category: Medicine

Effectiveness versus Efficiency in the Medical Consultation

One of the challenges in training registrars is trying to get over the apparent emphasis on the speed of consultation, or what you might call – churn. For doctors in clinical and rooms there is a set amount of time and a certain number of patients. You could argue that there might be more patients than a reasonable amount of time and yes one could take the approach that one will take as long as necessary to o deal with all the patient issues but reality dictates that if you take that approach you probably won’t actually see al that many people and the population might be less-well served as a result.

Bosses can get grumpy with their registrars is they only see a few patients in their clinic and the clinic runs over time. Equally so the registrars might feel they are taking too long or perhaps not being thorough enough.

Rule 1 should be that every consultation isn’t a so-called long-case. I like to say…if there is nothing wrong then there is not much to say. Rule 2 should be that the focus is on effectiveness not efficiency. By this I mean – did you identify and sort out the problem? You can still this in a timely manner – you just need to adjust the pace to the circumstances. In my experience patients don’t like to be rushed but on the other hand they are more concerned with having their issues addressed and if you can do this the time it takes is of lesser importance. Flowing on from this then Rule 3 must be ‘deal with the most important concern to the patient’ – this is perhaps the hardest part. For starters what the doctor thinks is important and what the patient thinks is important isn’t always the same. Secondly what the patient thinks is important isn’t always transparent….this is the ‘there’s one more thing doc’ discussion.

So in summary – work out what’s important and deal with it and move on. This is effective and efficient consulting for a resource poor reality. In other words, until we get more resources to support whole person care and the time-unlimited consultation ‘Don’t sweat on the small stuff’

A turn of phrase in oncology

Communication in medicine and perhaps especially in cancer care rests on the interpretation of words.

Today I had to deal with the retort ‘but your colleague said that the chemotherapy I had was the best available for my cancer….so isn’t what you are offering me now not as good’.

So let’s strip this down. ‘The best available’ comes with caveats – the best available chemotherapy (just ignoring some of the new drugs) for melanoma has between 5 and 15% chance of shrinking deposits of melanoma. It is clear that ‘best available’ – at least in the eyes of the prescriber – is not the same as saying the treatment is effective for everybody. A treatment can be the best we have for all-comers but in reality the overall results can be pretty poor. The big problem is that most treatments don’t work for everybody: I can only get around this by saying that a treatment is the best option (compared to other options) and that even though a treatment is the ‘best’ for all-comers there is no way of predicting, for most drugs, which person will be the one who benefits.

Because of these vagaries we also need to be aware that just because one treatment didn’t work it doesn’t mean another might not – it may be that second treatment is better than the first – we just don’t currently have the means to predict which was the right treatment in the first place.

The trick for oncologists and other physicians – pick your words carefully – or take the time to explain what you mean.

Are the Hallmarks of Cancer a Good Framework for Teaching Oncology?

One of the challenges in teaching medicine and in particular sub-specialty medicine is the sheer volume of information to be digested. The commonest refrain I hear about studying the discipline of interest, in particular from new trainees in medical oncology, is ‘I don’t know where to start’.

There are many potential approaches.

There is the traditional basic science to clinical science approach. For example starting with the relevant biochemistry, anatomy, etc and building up towards practice.

There is the problem-based learning approach which is good for clinical scenarios but perhaps doesn’t encourage an understanding of depth.

Another approach applies templates to diseases. For example if we consider breast cancer one can think about the epidemiology, screening, prevention, adjuvant treatment and treatment of recurrent disease. The same template could be applied to each cancer type. There are common themes and also variations and differences between each cancer….but the basic themes are the same.

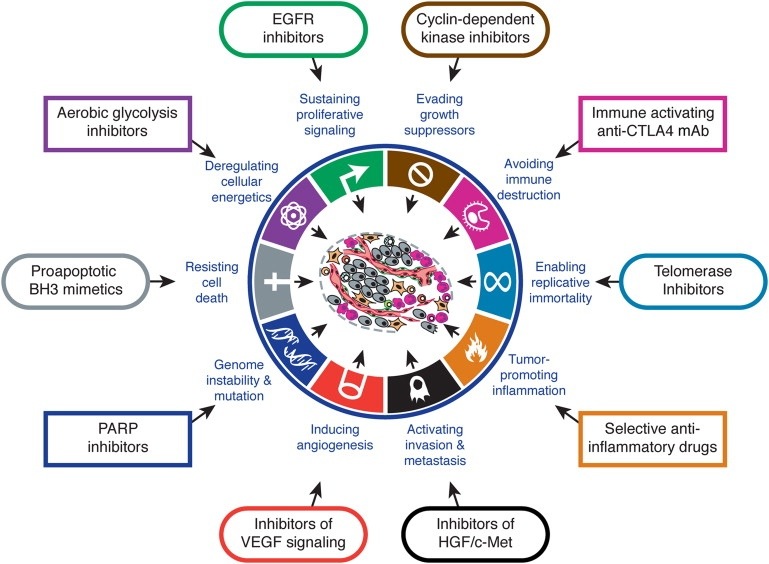

Arguably the latest approach is that of looking at the Hallmarks of Cancer as proposed by Hanahan and Weinberg in Cell (2000). The authors propose that there are key characteristics that cancers acquire that distinguish themselves from non-cancers. Although there are some criticisms that some of the hallmarks also apply to benign tumours, broadly speaking the concept provides a useful way for thinking about how cancers behave.

I think Hallmarks of Cancer is a useful framework for teaching oncology. What makes it useful if that you can think about high level concepts such as sustained angiogenesis or evasion of immunoregulation or self-sufficiency in growth signals or any of the hallmarks as having potential for application across the spectrum of oncologic interest: the hallmarks inform aetiology, diagnosis, prognostication, and potential treatment strategies. It provides a framework that facilitates both understanding complexity and engaging reductionism. It is the view from the plane that lets us know the concepts but enables closer examination.

Trainees need to familiarise themselves with The Hallmarks of Cancer and apply it to their studies.

Governance for safety and quality in health service organisations: where does the budget come in?

The first of the Australian National Quality and Safety Health Service Standards (2012) is “Goverance for Safety and Quality in Health Service Organisations”. There is little doubt that the processes of governance for clinical safety and quality are critical for health service organisations to achieving clinical excellence. But this standard seems to exist in isolation from the reality of running a health service organisation – in particular large public hospitals. Hospitals have budgets with finite sources of revenue and huge capacity to generate expense in excess of revenue.

Health services organisations should have governance processes that have consider safety and quality as well as the relevant budgetary considerations. By this I do not mean that cost should necessarily be taken in to consideration as a matter of primacy. Cost, efficiency, productivity, safety and quality all interact closely in a complex system and the governance processes should be designed to manage this complexity to produce the best overall outcome. Currently, in many institutions, these matters are considered in isolation and without understanding the whole system or model of care in question. The consequence is that when cost savings need to be made then it is largely expressed in terms of disinvestment rather than reviewing practice and considering reinvestment for net gain (or savings). The consequence is a cycle of deteriorating then improving budgetary positions trailed by deteriorating and improving performance in quality and safety KPI.

The governance models that will facilitate a global view of the organisation need to be models that reduce asymmetries of information. In too many organisations the managerial staff don’t understand the perspective of the front-line staff and visa versa. Too little of the data needed to manage organisations is used and when it is it is presented in ways that don’t favor analysis and interpretation. Activity based funding is an incentive to better use the big data available to hospital governance – it is time this data was readily available and we had training how to use it.

A step forward for overall health care in Australia is not just good governance for safety and quality but also for fiscal effectiveness.

Negotiating the religious obstacle course in end-of-life care and cancer care

As an upfront disclaimer I’ll note that I am an atheist.

Now that’s out of the way I’d like to think/write out loud about the problem of religion and spirituality in the care of cancer patients.

The role of religion in the overall outcome of cancer patients has been the subject of a lot of research and overall I’d have to say that the results are conflicting or inconclusive. There is no real evidence of improved outcomes with respect to the gold-standard – survival and/or cure. Spirituality and religiosity has however been associated with improved quality of life. There is mixed evidence, and this reflects my own experience, that religious individuals might choose less aggressive or more aggressive treatment at the end-of-life.

This makes it challenging for the clinician wanting to exploit religiosity for therapeutic ends. In some cases the religious person is sometimes reliant on their God for a miracle and to that end won’t accept a palliative pathway whereas in other cases the individual uses their faith as a crutch to help them deal with their impending death. Personally I feel that the latter pathway is the correct pathway from a theological perspective. My personal view is that many religious people don’t understand their religion (but again I’ll invoke my disclaimer at this point).

So what should the clinician do when it comes to intercalating a spiritual discussion into end-of-life care? The existing evidence suggests that access to spiritual care and support from spiritual care is low and also not provided by conventional medical systems. Yet it may play a role in helping individuals clarify their wishes. Should I as a clinician try to exploit spirituality to steer a patient to a conservative path of care? Alternately should I ask for a ‘religion consult’ in the same way that I might ask for a ‘cardiology consult’?

At the end of the day, and until there is more evidence, I think the clinician needs to tailor these discussions based on their gut instinct but I tell you now, it takes a lot of practice.

Things they didn’t teach in medical school: Part 33 Looking after colleagues and their families

Oncology can be a tough specialty with difficult emotional demands. These demands are compounded when you are called on to look after colleagues and/or their families. My earliest encounter with this was actually as a resident medical officer. I remember doing an evening shift and the nurses asking me to see the Professor of Surgery who had just been diagnosed with cancer and was due for a colonoscopy – the nurses were concerned that he had been drinking his bowel prep but hadn’t yet opened his bowels….I assured them he would. Later as a junior registrar I would accompany my bosses to see consultants who were hospitalised – this was just incorporated as a matter of fact into ward rounds.

Now I’ve moved up the food chain and am a boss myself I am called upon to look after the family of colleagues and no doubt I might have to treat colleagues for diseases in my specialty (rather than just their day to day ailments). The hardest thing I’ve had to do in this space is look after a family member of somebody who had been both a mentor and a work colleague. I’ve also had my own family members looked after by colleagues and whilst I’ve not necessarily agreed with the treatment pathways I’ve recognised that this is not my doctor-patient relationship to negotiate.

There is no doubt that you treat these patients differently. I don’t think this is actually providing better care or different for the patient themselves but you might make the extra phone call and provide more regular updates.

I think there are two key practice points to providing this care:

(1) actually, as much as possible, do not do anything different to your usual practice &

(2) remember, as always, to treat the patient, not the family (obviously whilst still engaging with them).

If you are a doctor with a family member being looked after by another doctor then there is a bit of quid pro quo…..don’t second guess your colleague and give them advice what to do – you trusted them enough to look after your family member in the first place.

Things they didn’t teach in medical school: Part 32 Coping with repetition, dealing with boredom

Medicine is an occupation that can provide enormously satisfying intellectual and creative challenges. But like any job where there are repetitive tasks it can have it’s boring moments. Becoming a specialist requires that one become expert through constant practice and repetition yet once mastery is achieved the continued day to day repetition can start to be frustrating. You might find yourself having the same conversations over again or performing tasks on auto-pilot. The problem with this is it can lead to laziness and mistakes, especially if boredom is combined with tiredness or is a symptom of burnout.

There are different ways to combat boredom. One of the reasons people get bored is a lack of challenges. I always know that my trainees are happy to become consultants and not to general overtime because they will no longer get called to see ‘chest pain’, well at least not as regularly. They’ve reached the point where this diagnostic task is no longer interesting – they need new challenges. So creating new challenges is a way of getting out of a rut. This might take the form of trying to improve your own performance – the perfectionist approach.

Another way to alleviate the boredom is the theme and variations approach. By this approach you do something routine in a different way…this can be just mixing up the way you explain something or you can consider it an experiment to find the best way.

The obvious way to deal with the non-creative tasks is to create opportunities for creativity. I’ll call this the portfolio approach. Many clinicians I know regard their clinical jobs as their bread and butter and they get broader satisfaction from their other roles such as researcher, teacher or even administrator. These other roles act as distractors and relief from the day job.

There are, of course, other ways, to deal with the boredom – regular breaks and holidays, learning new skills, and getting your work life balance right….and of course looking out for the next interesting patient problem to give you that ‘why I got into this in the first place’ feeling.

PS. my joke to my inpatients is that the commonest reason people die in hospital is boredom….don’t let boredom kill your career

Public hospitals also need governance standards for budgets and finance

So one of the Australian National health care standards is having adequate governance structures in hospital to support quality and safety of healthcare. Notably, however, public hospitals are more likely to appear on the cover of the newspaper for the state of their finances rather than quality of safety.

My hospital network has had its’ financial position downgraded by the Ministry of Health as unexpectedly it is in deficit – or at least more deficit than anticipated. So the consultants have been brought in to assist in saving dollars and recovering the financial position.

What bothers me is there is no governance standard for budgets and finance in our public hospitals. Now whilst I acknowledge that in a public health system we will never actually go out of business there is no reason why we shouldn’t have financial standards that resemble of those of corporations, but perhaps without the legal ramifications. The NGO I work with needs to comply with the Corporation Act and not trade as an insolvent entity. This concept can’t really apply to public hospitals but they should be accountable for their financial management.

Despite this the financial management of hospitals and the governance of this management seems to be ad hoc and left to the local sites. My experience of this is that all finance & budgeting is hospitals is forensic rather than planned and projected.

Hospital staff need to demand good governance practices for hospital budgets and ideally these standards should be harmonized between hospitals. I should be able to turn up to an administrative meeting and see a balance sheet that I understand and can react to in a timely and appropriate manner. As it stand we chase our tails.

Things they didn’t teach in medical school: Part 31 Advocacy

One of the things they didn’t teach in medical school is advocacy. There are different meanings for advocacy – in this case I refer to the broader meaning of advocating for patients and communities to achieve an end to their benefit. An example might be supporting the funding of a new drug or campaigning for increased resources for a hospital.

Simplistically advocacy can just be about being vocal but there can be problems with this approach.

To be an advocate it is important to be able to see all points of view so as being able to bring a cogent argument to the table. Often times advocates are dealing with political situations and positions and invariably these become polarised – it is important to diffuse this polarisation to get the party with whom one is lobbying to also be able to see the arguments in favour of your position. Advocates need to be prepared to compromise to achieve small but important wins rather than overnight revolution.

Advocates need to be careful about their motivations for lobbying. For example it is not uncommon for drug companies to ask doctors to provide support for a new treatment. If this happens there needs to be transparency about the reasons for lobbying and full disclosure of any conflicts of interest.

Similarly advocates need to be careful that their lobbying is not seen as some form of whistle-blowing – this is because some employment contracts prohibit this activity. In this case being part of a community of advocates is important. There is strength in numbers.

There are many tools for advocacy – the main one is conversation and the new medium for conversation is social media. Mastery of social media and branding the advocacy message is a new skill for the medical graduate advocate.

Could Taxing Alternative Medicine Help the Health Budget?

Australia, like many parts of the world, has an approach to alternative medicine and therapies that involves turning a blind eye to therapies that at face value seem harmless and able to be regulated with a lower level of rigour than conventional medicines. These therapies provide often provide false hope for patients with life threatening illnesses like cancer. Equally they are misleading for less immediately life-threatening problems. My wife is constantly receiving spam/junk advertising for weight loss programs that promise unrealistic weight loss – some of these have been in the press for serious side effects (and of course no weight loss except that attributable to the complications).

The alternative therapy industry is critical of the profit motive of ‘big pharma’ but these guys could equally be called ‘big herbal’. Australia spends approximately 9-10 billion dollars per annum on conventional medications and direct costs to patients accounts for 10-15% of this. Yet in 2005 more than 3 billion was spent on alternative therapies. If Australia parallels the US then current expenditure on alternative therapies might be 6 billion dollars or more.

A tax on these therapies – which bear minimal costs for development and proof of effectiveness and which rely predominantly on marketing for sales – could potentially raise enough funds to save 5% on the national medicines budget. There is no reason why a tax couldn’t be imposed – the government does it for tobacco, alcohol and luxury goods. And realistically – isn’t alternative medicine a luxury good.