Category: Uncategorized

What they didn’t teach in medical school Part 2: how the health system works

One of the things that wasn’t taught well when I went to medical school was actually how the health system works: in my case I’m referring to the Australian health care system but I’m sure the sentiment applies in other countries. Knowing how the health system works overlaps with how to run a business, which I’ll cover in a later post.

When you are studying medicine and even once you’ve graduated and working in the hospital you don’t really pay attention to how the health system works. The patients come and go and you do your best to look after them. It’s perhaps only once you actually have to go out and get a job, either in the hospital system or in private practice, that you start to care. When I refer to ‘how the health system works’ what I really mean is ‘how is health care paid for’. Once you get a job you are concerned with how you are paid and/or will pay other people. If you work in hospitals then you spend a lot of time listening to other people tell you you can’t do stuff because there is no money – even if what you want to do will result in real improvements and maybe even save money at the end of the day.

In Australia it is becoming even more important for medical students and junior medical officers to be taught how the health system works. As a result of the last round of health care reform the Federal government is phasing-in activity-based funding. So hospitals will be based on what they do according to a National efficient price. This sounds straight forward but in practice it is much more complicated. Hospitals won’t necessarily be getting paid on the basis of the activity they undertake. Governments must allocate budgets from finite coffers so the money local hospitals receives is based on projections, somewhat spuriously called targets. If the hospital undertakes more activity than predicted then unless it operates very efficiently it may end up over budget.

Medical students, junior and senior medical officers need to know about how activity-based funding works as they are the source of the the documentation about how much activity is being undertaken. Unless the doctor records not only the cholecystectomy but the co-morbidities of the patient and complications incurred during the hospital stay then ultimately the coding of the data to obtain funding will be inaccurate and inadequate. This in turn leads to inadequate models upon which the hospital activity targets are set.

These processes and in evolution and being rolled-out over the coming years. Doctors and their students need to become more familiar with how the system works so they can influence how their hospitals or practices are run and how the money is spent. Knowing how the system works will change how doctors work. Health care practitioners also need to be aware developments in primary care, such as the development of Medicare Locals. They will also need to keep up to date and the system is likely to change again. This is the decade of activity-based funding in Australia. The next decade might see a shift to process and outcomes-based funding and further changes to the way doctors practice.

I’ve only touched one major aspect of how the health system works. In Australia it is very complicated due to Federal, State and Local considerations. Medical schools will need to teach according to their local health care environment.

For more information see Activity Based Funding and the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority

Aaron Copland Symphony No.3

Listening to Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Neeme Jarvi playing Copland’s 3rd Symphony. What impresses me about Copland’s ‘American’ sound is the way the soundscapes could equally evoke vast plains of grass or metropolitan canyons.

Alfred Schnittke Symphony No.9, Dresdner Philharmonie, Dennis Russell Davies

Philip Glass Symphony No.9

What they didn’t teach in medical school Part 1: Behaviour Change

This is the start of an occasional series about stuff they didn’t teach me in medical school – and I suspect they still don’t teach this stuff. Where it was taught I suspect it was pretty poorly. These musings have come about because most of what I do now, that doesn’t fall into the categories of diagnosing or treating, wasn’t taught in medical school or as part of my specialist training. Some of these things include how to be an administrator, how to run a meeting, how to run a business, how to teach trainees and a whole bunch of stuff around fine-tuning the practice of medicine. I won’t necessarily have the answers about what to do to address these problems but recognition is the first step.

To kick it off with I’m nominating how to change patient behaviour.

Most of what I do on a day to day basis as an oncologist is prescribing medications to treat cancers. But there are a whole lot of behaviours that might also need to be changed or created to help my patients get through their illness. In the same way primary care practitioners need to be able to help their patients change behaviours in order to achieve preventative medicine goals.

Examples of behaviours and problems that might need to be addressed through behaviour change include tobacco, alcohol and substance abuse, obesity and poor fitness, poor adherence to medications or aberrant mechanisms for coping with illness.

I recall being taught how to detect these problems but not a great deal about how to address them. I suspect most busy doctors see their patients and go through the motions of discussing smoking cessation or some other behaviour change but either give up in despair or through lack of time or perhaps take the easy option and write a script for a patch or some other aid (which might help but should be part of a package deal not a one stop solution).

So every doctor dealing with these problems ought to read up or take a class on behaviour change. It’s all the rage in popular non-fiction right now with books on behavioural economics (Nudge by Thaler & Sunstein, Thinking Fast and Slow by Kahneman) and habit change (The Power of Habit by Duhigg) being in the best-seller lists.

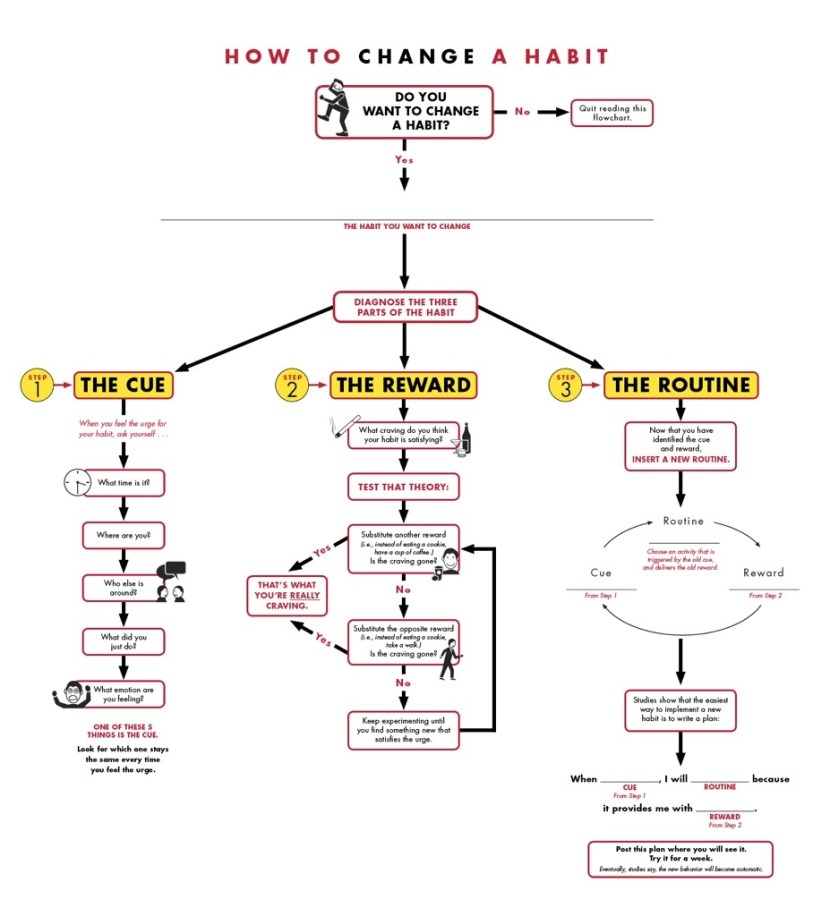

If you’re a doctor reading this then one way to learn about it is to try and change one of your own habits. Here a some clues how Charles Duhigg Habit Change Resources

Zoomusicology – is it for the birds?

Listening to Jonathan Harvey Bird Concerto with Piano Song played by Hideki Nagano with the London Sinfonietta conducted by David Atherton. For more on this work see Bird Concerto

You might also like The Piccolo and the Pocket Grouse

Edgard Varese Ameriques (1927)

Michael Tilson Thomas conducting San Francisco Symphony in Ameriques by Edgard Varese.

For more info see Ameriques

A New Year of Music

After a relative year off having completed the 365 String Quartets in 2011 I’m kicking off the musical journey again with an emphasis on modernism, 20th Century & contemporary classical orchestral music. To be liberal about the 20th Century I’ll listen from the period of Brahms & Mahler to the present.

Kicking off the year is Detailed Instructions (for Orchestra) 2010 by Nico Muhly, played by the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Alan Gilbert.

The Curator Unplugged – Training Future Doctors in the Era of Electronic Decision Support

One of the key problems facing educators in medicine today is how to train future doctors in medical decision making in an emerging era of electronic decisions support in EHR (electronic health record).

Training prescribers how to prescribe mHealth apps

Sometime soon your doctor is going to prescribe you a mHealth app for your smartphone. There’s a 1 in 3 chance you already have one on your phone – for tracking calories, weight, exercise, your smoking, your blood sugar or our mood. How will you or your doctor know which is the right app?