Category: Uncategorized

Sibelius Symphony 3 & 4

Sir Colin Davis conducting Boston Symphony Orchestra in Sibelius Symphony No.3 in C Major, Op.52 and Symphony No.4 in A Minor, Op.63

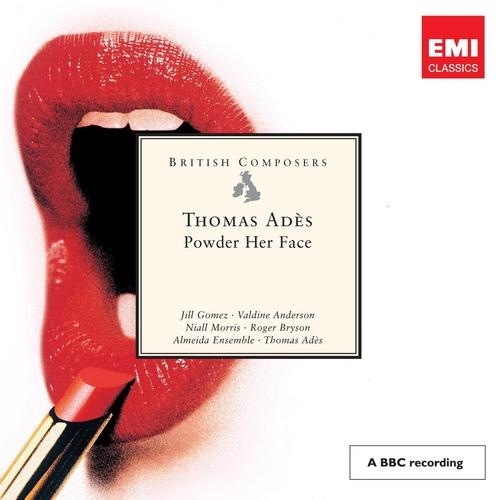

Thomas Ades Powder Her Face

Powder Her Face, an opera by Thomas Ades

Audio CD: Conducted by the composer with the Almeida Ensemble and performed by Jill Gómez, Valdine Anderson, Niall Morris, and Roger Bryson. Recorded 1998, released 1 October 1999. (EMI: CDS5566492)

Anton Webern Symphony Op.21

Accountability, Blame and Empowerment

A lot is being made at the moment about the growing patient/consumer empowerment movement. Empowerment and engagement is seen not only as a step to improving the health of individuals but also lowering total health care costs.

It is interesting to see these two contrasting views re-posted on the KevinMD site:

Stop blaming patients for not doing enough to stay health

&

Make patients more accountable for their health

These views highlight the complexity of empowerment. Yes people should be responsible for their health. At the same time incentives and penalties for taking/not taking responsibility should not be discriminatory.

One way to approach this is to de-emphasise the individual and look more at cultural and societal factors. If we look at the obesity epidemic for example – we’ve got here because of the marketing of myths about diet and metabolism and industries built around encouraging us to eat foods that predispose to insulin dysregulation irrespective of the total caloric intake. To address this needs changes in food policy and re-education. We aren’t going to cause a reversal in the obesity epidemic by penalising people for being fat.

The other thing is empowerment shouldn’t be burdensome. Empowerment should be about creating habits that people don’t have to think about. As I saw on twitter yesterday – what we need is to get people addicted to health.

Martinu Symphony No.6

BBC Symphony conducted by Jiri Belohlavek playing Martinu Symphony No.6

What they didn’t teach in medical school Part 3: Knowledge (or Information) Management

One of the things they don’t tell you at medical school is that one of your major jobs will be managing information or knowledge management. All though training the implication is that you have to know a lot of stuff to be a good doctor. Well that is true but in reality only a few of us know (or think they know) everything – I’m definitely not one of them. Teaching others now it is hard to communicate the message that you need to be exposed to everything but not know everything. This problem is compounded by the fact that we are dealing with a google-generation. Medical students google stuff on their smartphones in the middle of my tutorials – fortunately for me and unfortunately for them they still often don’t get the answers. There is an emerging myth that you don’t need to know stuff if you can look it up – this isn’t very time efficient and of course you need to know what you are looking for and be able to interpret it.

As I see it there are 4 categories of information.

(1) Stuff you need to know without looking up – or thinking fast information. Examples are doses of medications prescribed on a daily basis.

(2) Stuff you need to know about and need to be able to access easily through a personal filing system or through readily accessible websites or conventional sources. An example might be a chemotherapy protocol that you know about but don’t use everyday and you need a reference or webpage to check the details of the protocol.

(3) Stuff you think you might need to save for a rainy day. You think you might need it but probably not on a routine basis.

(4) Stuff you need to should know exists but isn’t important enough to file personally and can be obtained by searching online via literature databases such as Medline or Pubmed, or via google. An example might be information you look up only when you give a talk e.g. the latest stats on a particular problem. This category arguably includes everything else you don’t even know you need yet.

When I first started oncology training I had a filing cabinet full of photocopied journal articles filed according to topic. I also started using the reference management software Endnote. I still use this but mostly if preparing manuscripts or references for a publication.

The technology changed a lot in the last decade. For a while there were a lot of USB drives. Now favourite references can be stored in the cloud using managers such as Connotea (which is about to be phased out) and CIteuLike. One isn’t always online and so computer-based platforms such as Papers (from mekentosj.com) are useful for storing and searching pdf files (bye bye filing cabinet).

These days my favourite piece of software, Evernote, is cloud-based and syncs across multiple devices including my laptop, iPad and iPhone. The beauty of Evernote is the ability to send yourself any piece of information – not just journal articles – either by cutting and pasting, web clipping, taking photos, by emailing, scanning (I use a Canon P-150 portable scanner which scans straight into Evernote), writing using an Echo smarten, or simply by making typed notes. The notes can be organised into specific notebooks or other buckets and can be tagged using your own tags to allow complete them to be searched and sorted. Everything in my category 2 & 3 goes into Evernote.

There is other software that can be used including your email client. Some people use Dropbox but personally I find Evernote the best for merging knowledge and time management related activities – which so often overlap.

The most important thing is to have a system that works for you. Using the system will help you sort out what you need to know and what you need to know how to find.

Med School needs to teach this stuff – in fact all schools do.

Recomposed by Max Richter – Vivaldi:The Four Seasons

Listening to Recomposed by Max Richter – Vivaldi:The Four Seasons. A contemporary exploration of the Four Seasons in the hands of composer Max Richter. Love the description of Antonio Lucio Vivaldi’s music being molecular – i.e. suitable for tearing down, reconstruction, reconfiguration and reinterpretation.

Daniel Hope on solo violin. Konzerthaus Kammerorchester Berlin conducted by Andre de Ridder on Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft – Decca.

Scriabin 3rd Symphony

Le Divin Poeme, or the 3rd Symphony by Scriabin

Population Health or Personalised Health in Preventive Medicine

One of the common comments about modern healthcare is that we would do a lot better to focus on prevention of disease rather than treatment of disease. The argument goes that we could reduce the cost of healthcare by preventing diseases in the first place and through promotion of ‘wellness’. In principle this sounds like a fair approach but are we sure that this will be the case?

Many effective prevention strategies are already in place: clean water and food sources, fluoridation of water, vaccination against childhood illness, and screening for some forms of cancer. Many of these activities are also cost-effective. These are population level strategies.

But many for many other conditions the role for prevention is less clear. Populations turn out to be heterogeneous and many conditions, whilst common, are actually not likely to occur for any given individual. The way around this is to identify who should receive a preventive intervention by risk stratification. The simplest example is smoking. Smokers are approximately 25 times more likely to develop lung cancer than non-smokers. Lung cancer and other smoking related diseases contribute substantially to the economic burden of disease. So it makes sense to promote smoking prevention.

On the other hand – not every smoker develops lung cancer (‘uncle Eddy lived to 90 and wasn’t sick a day in his life’) and 10-15% of lung cancer patients are non-smokers. So as an intervention smoking prevention will not necessarily eliminate the development of new cases (like universal polio vaccination) but it will have a substantive impact.

One way to increase the chances of correctly identifying ‘at risk’ individuals for any given disease is to obtain more in-depth information about risk factors. For many diseases this will involve genotyping or knowing the genetic make-up of a person. It is now possible to sequence the whole genome of individuals and commercial ventures undertaking genetic screening for predisposition to common conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease already exist.

With the possible exception of public policy around obesity prevention is possible that most of the population health measures to prevent disease are already in place. The way to move forwards is to gather more information on genetic predisposition to disease in order to target efforts at prevention. Some of the genetic factors will provide targets for intervention. Some genetic factors will cluster together – e.g. a cardiac risk profile – and will help direct prevention. Whilst this is the is the logical approach it may not be as cost-effective as the population health approach, but then the population approach isn’t necessarily applicable to the problems not yet tackled.

Sibelius 1st Symphony – cooler than where I am right now

Jean Sibelius Symphony No.1 in E minor, op.39